My colleague, Ben Woo, has been teaching our first year Introduction to Communication Studies course this year. During the past few months he has invited colleagues from our department to deliver guest lectures related to different topics discussed in class. Since I ended up writing the lecture I figured it may as well appear here as well, so here it is – my lecture on sexting. Note that Ben had students read the debate between Amy Adele Hasinoff and Nora A. Draper on whether teens should have the right to sext (see Part 3, issue 3 in Greenberg and Elliott’s Communication in Question).

I am going to spend the majority of my time unpacking the image on the left and conclude by turning to the image on the right. Both come from education campaigns that aim to shift public attitudes and behaviours.

On the left we have a campaign coming out of Australia, developed in partnership by Youthlaw and the South Eastern Centre Against Sexual Assault. Let’s take a closer look – I’ll zoom in on the top half of the image.

Ok, what do we see here? The story begins with a man pressuring a woman for photos. This gendered framing – men asking women for nude photos – is common. Peer pressure, coercion – it’s all part of it – but research tells us that girls and women are adversely affected.

- We have all been socially programmed to adhere to a broad set of social norms. Rules we ought to follow and expectations others ought to have of us. And so we wear clothes in public, we leave space between ourselves and the person next to us when sitting on a park bench, we can ignore people begging for money on the street. These social guidelines and expectations are not always designed to increase our empathy for others – but they do have a tendency to keep us in our prescribed boxes.

- So if you grow up as a boy here in Canada, you will have come across the expectation that you become sexually active. And you are by no means encouraged to stop at one partner. Sexually active boys are to be admired and ‘rated.’ It may be that your peer group rebelled against this expectation – there are certainly antidotes to the prevailing cultural logic.

- Now, if you grow up as a girl here in Canada, becoming sexually active can go hand in hand with a label that can be damaging and very hard to shake off: I’m talking about being called a slut.

- Same activity – having sex – different social outcomes based on whether you are a boy or a girl. Boys are expected to sleep around. Girls are expected to save it for someone special. Rules, rules, rules. Who made these up anyway?

- Well, that’s another discussion. The point is not that boys have it better. The point is that everyone gets put into a box and feels pressure. Everyone faces gender-specific risks too. Girls cannot speak openly about their sexual activities and practices. Boys can be excluded from their peer groups if they do not brag about sexual experiences.

Now I have to pause. And I have to pause because if I don’t I’ll have committed a fatal flaw. I’ll have been another person in your life – if only for this brief 30 minutes – who has contributed to your understanding of what is normal. When we speak about boys and girls or men and women and carry on as though we’ve just covered the entire human population we are excluding everyone who does not fit into the neat and tidy categories of male and female. We erase everyone who does not fit and we make it normal – again and again and again – to understand the world as a binary. Let’s bring trans men and women into the room. Let’s imagine youth in the beginning of a transition to another gender or youth who are questioning their gender or youth who define themselves as genderqueer or two-spirit – neither boy nor girl. Now what expectations do we have for sexual activity? Now what risks are we talking about? Trans and gender-nonconforming folks – that is, anyone who doesn’t fit either the male or female box – are already dealing with an enormous amount of social stigma and beyond that everyday reality, suicide rates are significantly higher than rates for cisgender folks – I’m talking about you if the gender your doctor assigned you at birth matches the gender you feel you are. And if you happen to fall into other marginalized social categories as a trans or gender-nonconforming person – like if you are a person of color or if you have a disability – the rates of violence and discrimination you are likely to experience in your lifetime greatly increases.

Amy Hasinoff’s chapter – the YES answer to the issue, should teens have the right to sext – did an excellent job of informing us that the consequences for sexting are not distributed equally.

“The illegality of sexting does not just affect girls excessively; it also affects queer youth, racialized youth, and low-income youth” (2013, p. 161).

She goes on to say that these groups of teens receive more severe punishments in part because their behaviours are watched even more closely – inspected and dissected and judged more harshly – than straight, white, middle- to high-income youth. So what I am saying is that these social norm guidebooks in our heads are not applied equally. There is not one book and there is not one category of teenager.

Now let’s return to the campaign.

So again we are presented with this image of a man asking a woman for a sext. Research by Jessica Ringrose and her colleagues coming out of the UK tells us that sexting also involves specific types of pressures that relate to expectations about how we are supposed to look – big muscles? Big breasts? Thin? These pressures about our bodies are also tied to what Ringrose calls “globalized consumer-oriented cultures of consumption,” that also teach us about status. She discovered that one way for boys to gain status among their peer group is to solicit, collect and distribute sexual images of girls’ bodies. Having a collection of 30 images of girls becomes a performance of masculinity.

Now stop and think about what it means to be masculine for a moment. What does that look like in your head? What is a so-called ‘real’ man?

Is this part of it? Is it tough to ask for nude pics of girls and then spread them around to big yourself up? Is this what masculinity is all about?

But wait a minute. Let’s not forget one of the most important lines from Amy Hasinoff’s chapter:

“While the aim of consensual sexting is pleasure and communication, the goal of abusive sexting is often to harm and humiliate someone” (2013, p. 162).

There is not just one type of sext. Many people – old and young (and Nora Draper’s chapter emphasizes this as well) – are into their sexuality and are into sharing it with their partners. Many people are into pleasure. Sexting can equal pleasure. The whole debate in the two chapters you read relates to whether teens should have the right to sext. In my mind, the focus in this question shouldn’t be whether teens should have the right to experience pleasure – even if it is, GASP, of a sexual nature. Let’s stop being prudish about sex and pleasure. Enough is enough – silence on these issues is so very damaging in so many ways. The question then – whether teens should have the right to sext – in my mind, relates much more to the failures of our legal system that penalizes people because it has such trouble dealing with nuance and complexity. And it relates to the question of the role of new technologies and how we use them and how society and technology interact with one another and shape problems like consent and privacy.

Now you see I wasn’t kidding when I said I would go through the first campaign slowly – maybe painfully slowly. Let’s move to the second half of the image.

First, this ‘respect me don’t sext me’ tagline has to be noted. This framing completely erases consensual, pleasurable sexting. But, moving on, probably the biggest problem with sexting happens right here. He shares it. She cries. It is seen by everyone, she faces the social and perhaps even legal gendered consequences, and the photo stays online forever. Did he think she wanted him to share it? Did he show it to just ONE FRIEND – one friend who would never ever go behind his back not ever, never? Whatever the circumstances, abusive sexting is a symptom of profound social problems. We can only resolve this through profound social change – and the final campaign that I’ll get to in just a moment is one attempt in this direction.

But first: I have to linger on the ‘share with friends now’ button. This button only exists because lines of code were entered by a computer programmer. A computer programmer, likely following instructions from a superior, designs the application this guy is using on his cell phone in a thoughtful and specific way. The programmer works for a company that makes design decisions that are largely motivated by the desire to make profit. Encouraging or nudging a user to share an image with friends is likely designed to promote the use of that user’s cell phone, to promote perhaps the use of a social networking site like Facebook. Images are particularly valuable to Facebook since they tend to generate a lot of page views on their site – people click on pictures, they don’t always click on status updates – and they work towards keeping users on Facebook longer. This means more opportunities to show advertisements and make profit, and generally speaking more commitment to Facebook by the user since they are spending time on the site.

What I am getting at here is that technology isn’t neutral either. People design technology. And people have – as we’ve already discussed – norms and values and stereotypes and all the rest of it and these social elements get baked into technologies.

Ideas about gender, race, class, disability, and many other social categories get baked into design practices but I offer you this example since it is widely referenced.

While we are on the general topic of gender and design, I have another example.

Frontal crash-tests for automobiles are conducted to assess safety. Dummies are used in these crash-tests, but for three decades an average male dummy was the only shape positioned in the driver’s seat, presumably under the assumption that it is a man who would be the likely driver. Of course the average male dummy will not accommodate every man’s size but even more so it does not accommodate the size of people who are not men. Studies have shown that female drivers are 47% more likely to have a serious injury in an actual crash in comparison to male drivers. In 2011 female dummies became mandatory.

Coming back to sexting, my point is that technological design is another avenue for us to explore when it comes to combating abusive sexting. Design decisions could include making sure that the sender of an image can decide if the person who receives it can send it. Images could be protected from screenshots, social networking sites could deny posting an image until consent from all parties has been received. These design suggestions are not perfect but it is worth our time to keep technological design in the equation, along with the cultures that surround the tech industry and contribute to the lack of diversity of computer programmers and engineers. Today there are a number of programs geared towards getting girls and women interested in computer programming and engineering – along with science and math. But it is not just women who are underrepresented in these industries.

Finally, I will now turn to the second campaign to make my last points.

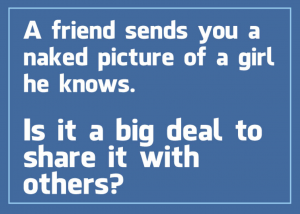

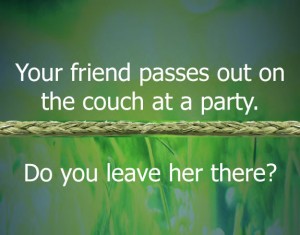

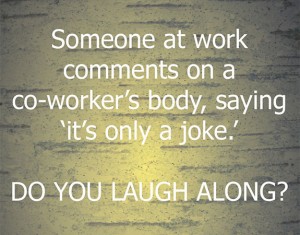

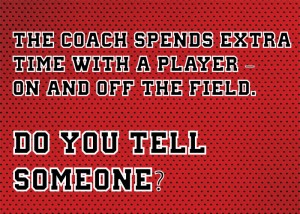

This campaign is called Draw the Line and is based in Ontario. The value of a campaign like this is that it focuses on the bystander. A bystander is either involved in a bad situation on the sidelines or witnesses something and could intervene. Campaigns like Draw the Line put the onus of responsibility for preventing abuse on all of us, asking us to help create social change, a necessary component towards tackling the roots of social problems like abusive sexting.

To sum up, abusive sexting is the social problem here, not consensual sexting. The consequences for abusive sexting are not equally distributed across all people who send sexts or distribute them – marginalized groups experience much more severe penalties both socially and legally. Pressures for sexts and sexual experiences more broadly are also experienced differently. People with disabilities are invisible in most of popular culture and when we do see them, they are often presented to us as asexual. If we read disabled bodies as ‘undesirable,’ what does that mean for their participation in pleasurable sexting? For trans and gender non-conforming folks, they are at risk of greater violence if recipients of sexts misgender them and go on to feel threatened and lash out. The roots of social problems like abusive sexting are steeped in issues of consent and privacy but they are also deeply tied to how we think about sexuality and power relations more widely.

I will leave you with three more examples from Draw the Line to consider when thinking about abusive sexting and the many everyday scenarios that are deeply intertwined with the roots of this social problem.